Motivation for Isolation

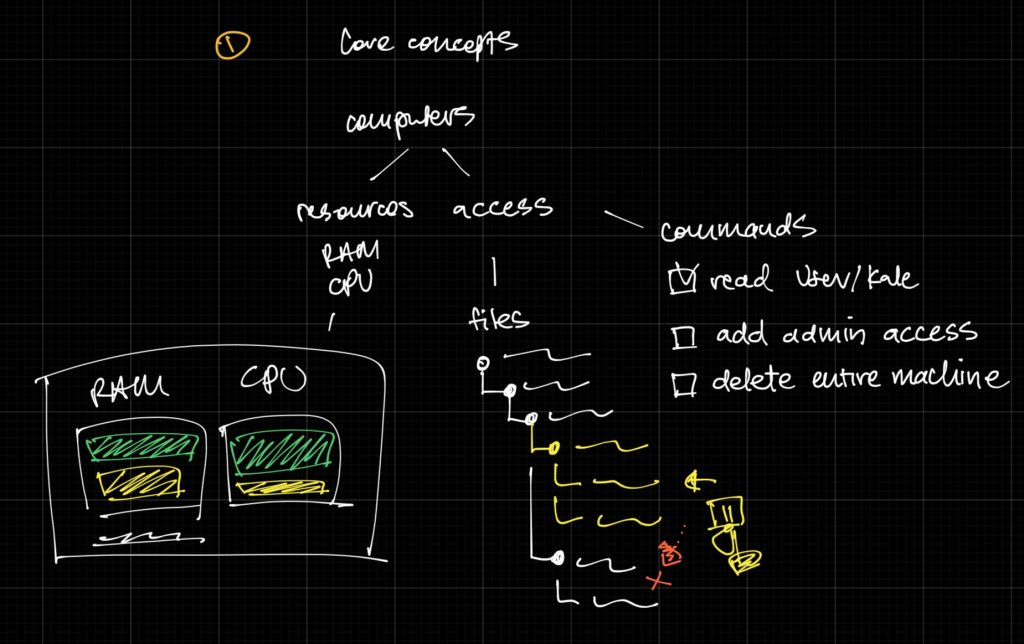

Why isolate? Let’s consider two core concepts of a computer: Resources and Access

A computer has resources like RAM, CPU that allow programs to compute and complete. These programs have access to files in your file system and executable commands. Each program has difference privileges – program A may write to the database but not be allowed to delete the computer (rm -rf dot).

Hello Isolation. In cloud environments, it has grown popular to share compute by occupying partial space on shared servers. This sparked the need to create isolation of these resources and access among many customers.

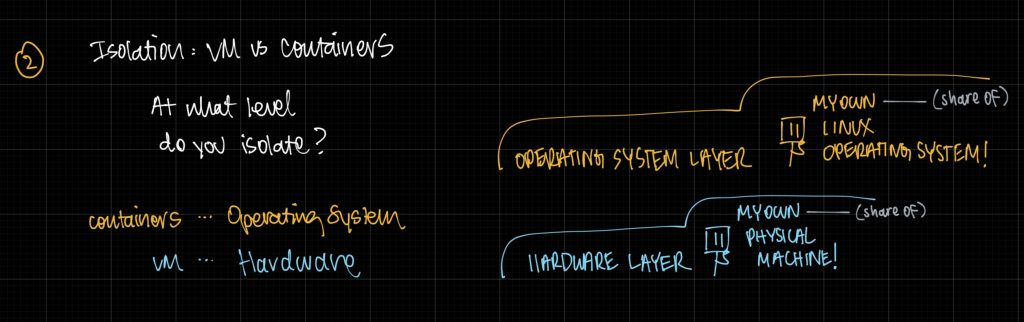

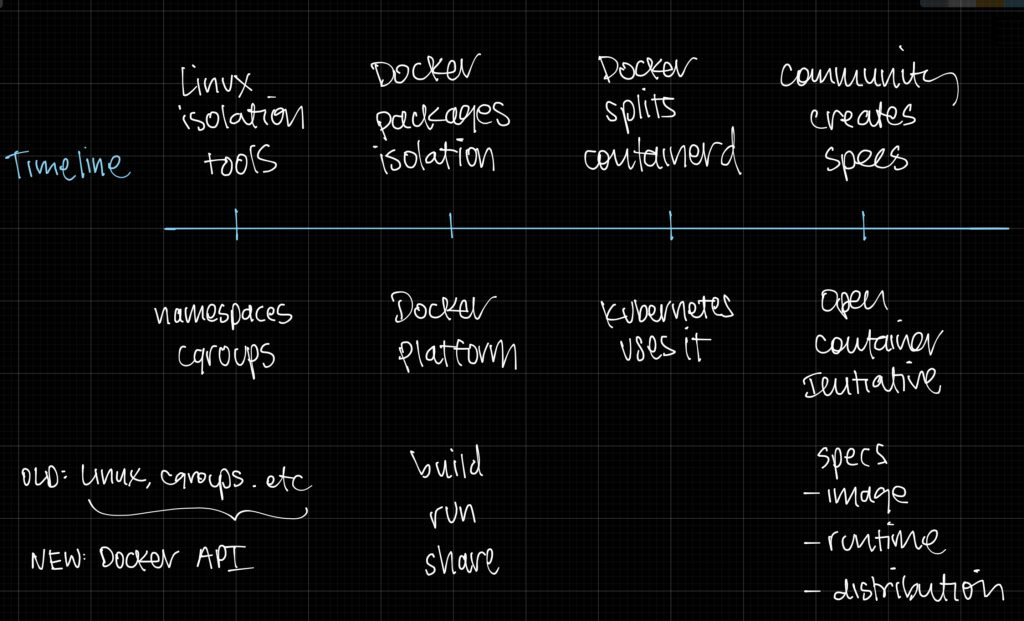

History of Isolation

In the past cloud companies started with isolation on the hardware level (you get X RAM and Y CPU to run your own OS). This meant users had to set up their own Operating System. One day, we realized Linux runs 90% of the web servers in the world and if we assume a shared Linux OS, we can share the computers with a commonly installed OS.

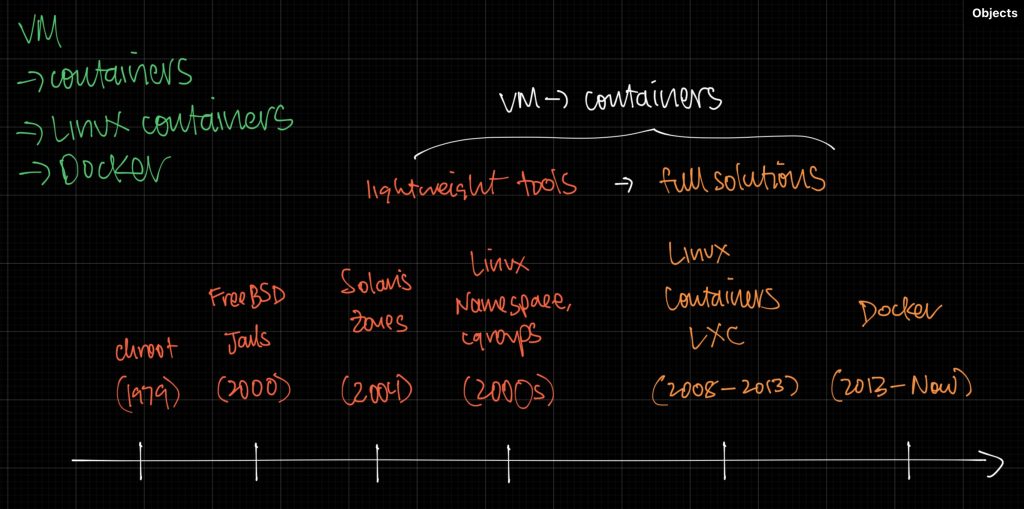

VMs -> Docker was not instant.

- The industry created more lightweight tools over time. “chroot”, FreeBSD Jails, Solaris Zones, Linux namespace and cgroups. Many teams in large tech companies built their own tools in private.

- Linux Containers (LXC) was released as a full solution.

- Docker was introduced in 2013 at PyCon and its many advantages and developer experience changed software engineering forever.

Docker has progressed

- Docker was built on Linux isolation tools (namespaces, cgroup) and this became the Docker Platform. Progressive, parts of Docker evolved.

- Docker split “containerd” which is now used by Kubernetes to run containers

- The Open Container Initiative created specs to standardize across platforms which helped avoid vendor for the industry

- image spec

- runtime spec

- distribution spec

Motivation for Reproducible Builds

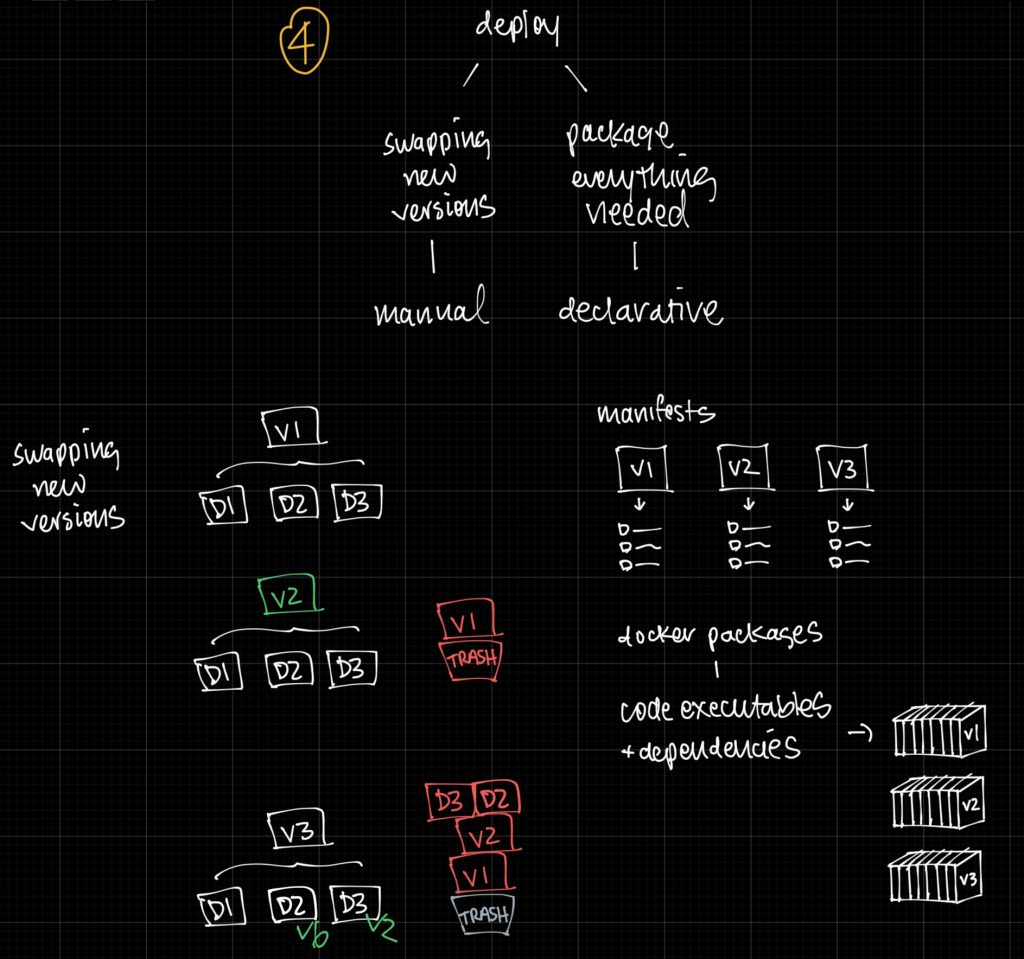

The Dev Lifecycle is: Write Code <-> Deploy

Deploying can be manual or declarative

An example of manual deploy:

- You push code, say V1, which has dependencies D1, D2, and D3.

- When new code is written, you need to deploy V2 – this means getting your code on the server witch git pull, rsync, ftp etc…

- When new code is written again, you need to deploy V3, but remember that to update the dependencies to D2^V6 and D3^V2. AHH!

An example of a declarative deploy:

- Your devs maintain manifest files which contain all the steps to deploy the app.

- “Build” those “images” and publish them to the cloud.

- To deploy, you pull the images and run the image. Done. Everything is included.